Seán Thomas Kane

State Historian

A History of the Kansas Irish

Beginnings

The story of the Kansas Irish is one of a people seeking a new home far from their native shores where they and their children could experience better opportunities than anything available to them at home. The largest wave of Irish immigration to Kansas came early in the settlement of the region by the United States between 1850 and 1900 followed by smaller waves of migration by Irish Americans from other states into Kansas since 1900. Irish Kansans experienced many of the state's most historic early moments, and many more helped build the cities and towns that dot the Kansas countryside, creating new homes and communities on the prairies.

The first two Irish Americans to visit Kansas were Patrick Gass (1771–1870) and George Shannon, (1785–1836) both a sergeant and a private in Lewis & Clark's Corps of Discovery that left St. Louis in June 1804 to travel up the Missouri River searching for a water passage to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition camped at Kaw Point on the night of Tuesday, 26 June 1804 until the morning of Saturday, 30 June, where the Kansas River flows into the Missouri, its waters heading southeast towards the Gulf of Mexico.[1] Gass was the son of Irish immigrants who arrived in colonial America before the Revolution. Gass was raised in southwestern Pennsylvania while Shannon immigrated as a young boy with his family who were among the first Irish settlers in southern Ohio.[2] The Corps of Discovery marked the beginning of American colonization of the Louisiana Territory, only recently purchased from France. Kansas was included in these lands, and while there may have been Irish missionaries, mercenaries, or merchants who visited the lands today a part of the State of Kansas traveling under the flags of either the King of France or the King of Spain in the centuries before 1800, their names remain elusive to the historical record.

Patrick Gass (1771–1870)

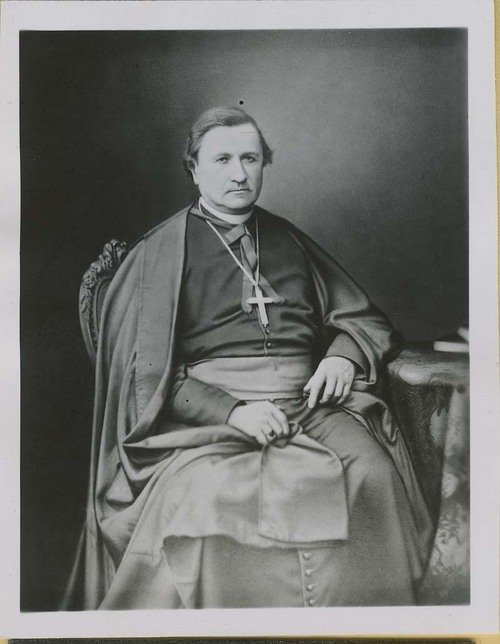

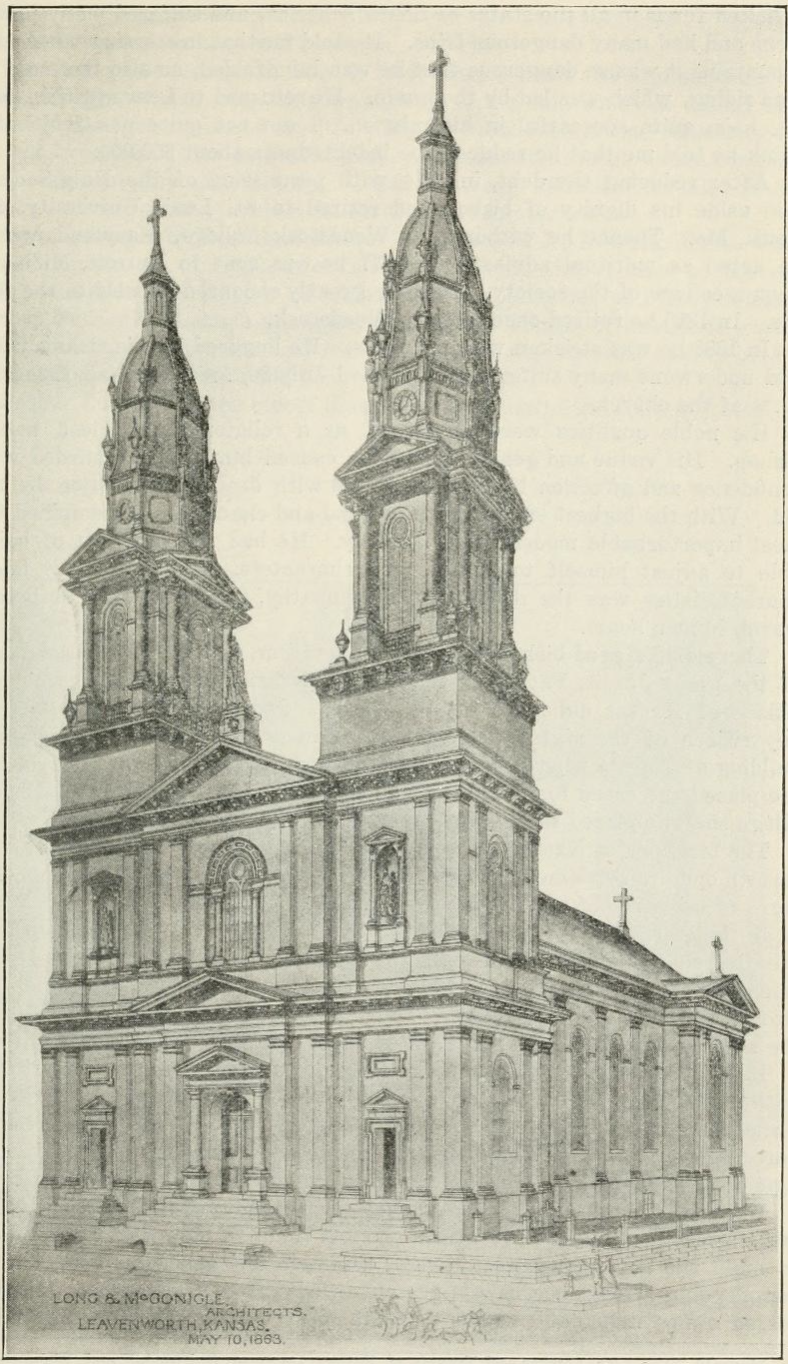

A similar story appears in the founding of another city about 20 miles upriver from Kansas City, whose first settlers arrived in 1854 "and pitched their tents in a pleasant place near the protecting guns of Fort Leavenworth" where they established the City of Leavenworth. Among these settlers were Irish immigrants whose spiritual needs were ministered by the Savoyard Jesuit Jean-Baptiste Miège (1815–1884) who was appointed by Pope Pius IX the Vicar Apostolic of the Indian Territory in 1850, in which capacity he ministered with the Jesuits at St. Mary's Mission northwest of modern Topeka. Later in 1857 Miège was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Kansas as more settlers from the East and Catholic immigrants from Europe arrived in Kansas Territory.[4] Miège established the cathedral parish of the Immaculate Conception in Leavenworth in 1855, where a decade later an Irish priest named Thomas Ambrose Butler (1837–1897) from the Archdiocese of Dublin was assigned to minister to his fellow Irishmen in Leavenworth. Butler described the Leavenworth cathedral as "one of the finest buildings in the West," which dignified the city's Catholics.[5]

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Leavenworth City, Kan., Kansas Historical Collections, 9 (1905–06), 157.

The main waves of Irish immigration to Kansas began in the 1840s as American settlement of the Missouri-Kansas borderlands opened. In 1845 one of these Irish immigrants arrived in Jackson County, Missouri to become the first pastor of St. Mary's Church in Independence and the new priest of the French church of St. Jean-François Régis along the bluffs above Kaw Point in what became the Quality Hill neighborhood of Kansas City. This priest, Fr. Bernard Donnelly (1810–1880) soon built a brickworks in the young City of Kansas City which attracted more Irish immigrants who had just arrived in Baltimore and Philadelphia to travel west and help carve the young city out of the bluffs of the Missouri River and to build many of its oldest brick buildings.[3]

Statehood

As Kansas moved from territory to statehood at the turn of the 1860s the region suffered a brutal prelude to the larger Civil War that would follow. This period known as Bleeding Kansas saw the creation of many of the Sunflower State's founding legends. Among these is the story of an Irish immigrant named Pat Devlin. Born in 1825, he likely arrived in the United States during the Great Hunger of the 1840s, finding his way westward to the Kansas Territory. Devlin settled in Osawatomie in July 1855 and lived in Miami and Linn Counties for at least the next four years.[6] Over that time Devlin earned a reputation as a thief and regular acquaintance of the local lawmen. He nevertheless proved useful to the Free State cause in the leadup to Kansas statehood, experiencing the Battle of Osawatomie in August 1856 in which the town was looted and burned by pro-slavery border ruffians led by John Reid.[7] Devlin's name appeared on a muster roll in Company C of the Burlingame Rifles, a Free State unit, in 1857 as a 4th Sergeant.[8] Yet it is an anecdote about Devlin that earned him his greatest fame. In a book later published in 1894, the Kansas State Senator T. F. Robley recounted an exchange he had with Devlin in February 1858 as the Irishman returned from a raid with a company of free-staters against a pro-slavery settler named Van Zumwalt, who was "said to have perpetrated several murders of free-state men." On his return, Devlin cheerily remarked to Robley that he'd been "jayhawking." Robley continued, recording Devlin's words in a phonetic spelling "Well, sor, in ould Oireland we have a birud we call the jayhawk, that whin it catches another birud it takes a deloight in bullyragin the loife out ov it, like a cat does a mouse."[9] Devlin is one of several people considered to be the originator of the term Jayhawk at a time when Kansas's identity was being created out of the Free State cause.

The fighting during Bleeding Kansas saw its peak with the burning of Lawrence in 1856 by William Quantrill and his pro-slavery raiders from Missouri. This attack, now etched into the long memory of the state and the source of the modern college Border War rivalry was witnessed by one Irish immigrant named Bernard Donnelly (not the priest) and his family. A history of Lawrence's St. John the Evangelist Parish written in 1904 by Donnelly's daughter Mary records that her family welcomed the first pastor of St. John's Church, Fr. J. J. Magee, into their home on Rhode Island Street to celebrate the parish's first Mass in October 1857.[10] When Quantrill's returned to Lawrence to attack the city a second time in 1863 during the Civil War, the city's ministers took shelter in St. John's under the protection of Bishop Miège who was visiting the parish "to administer the sacrament of confirmation the following day." Quantrill distrusted clergymen, and it took Miège's intercession to the Confederates to keep them from burning St. John's and the people hiding within.[11]

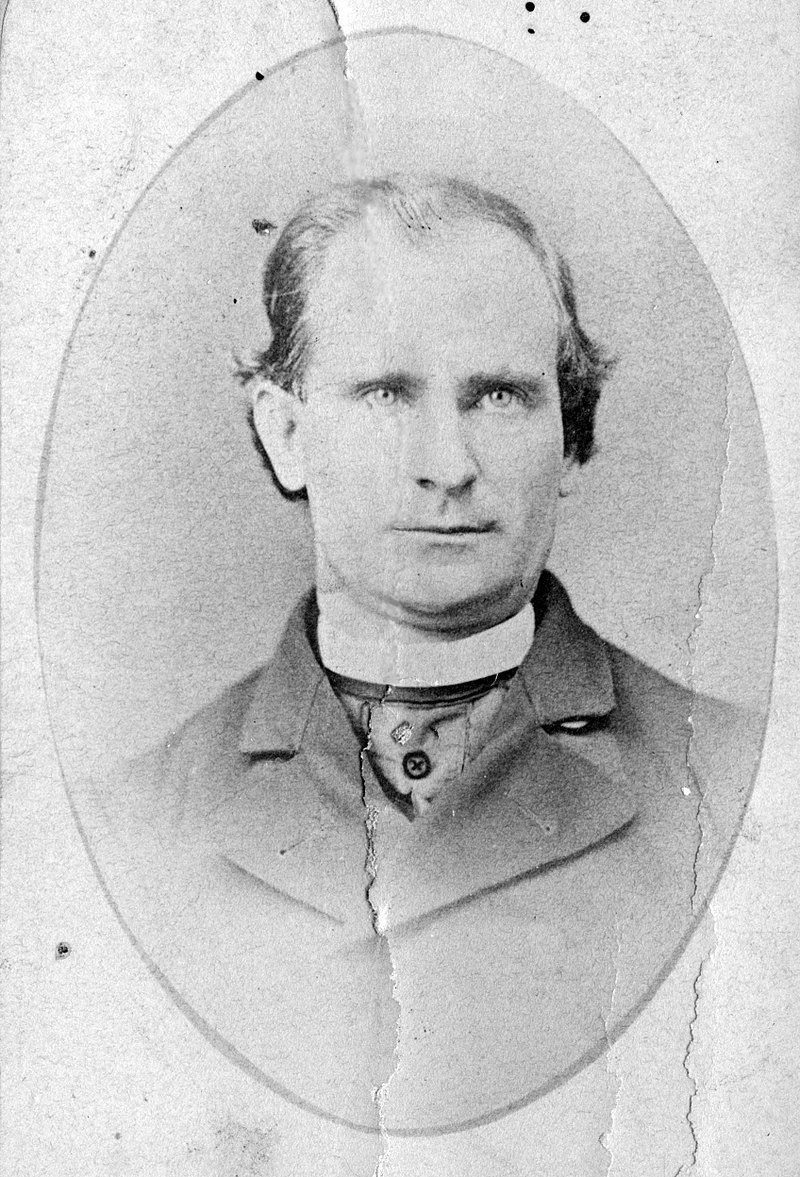

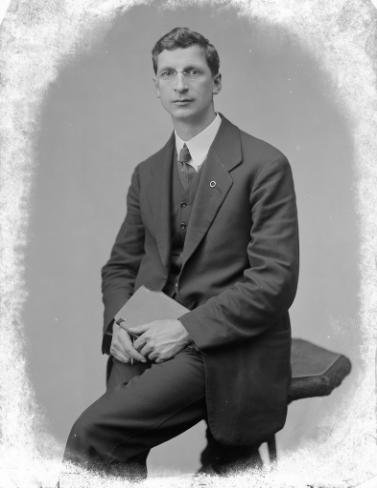

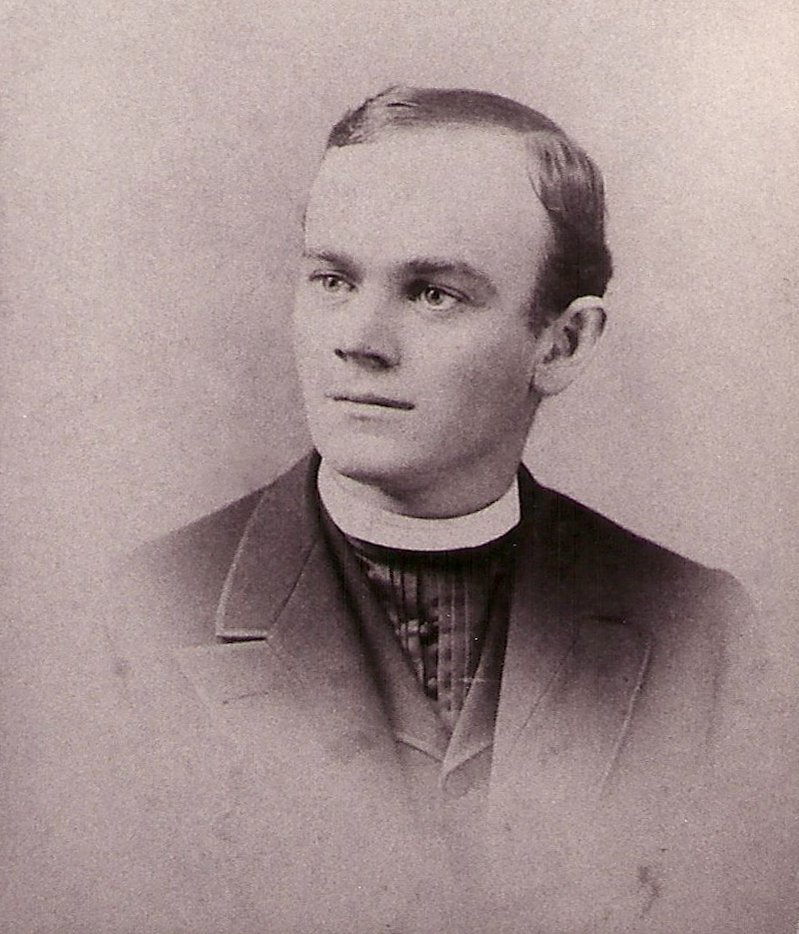

Fr. Thomas Ambrose Butler (1837–1897)

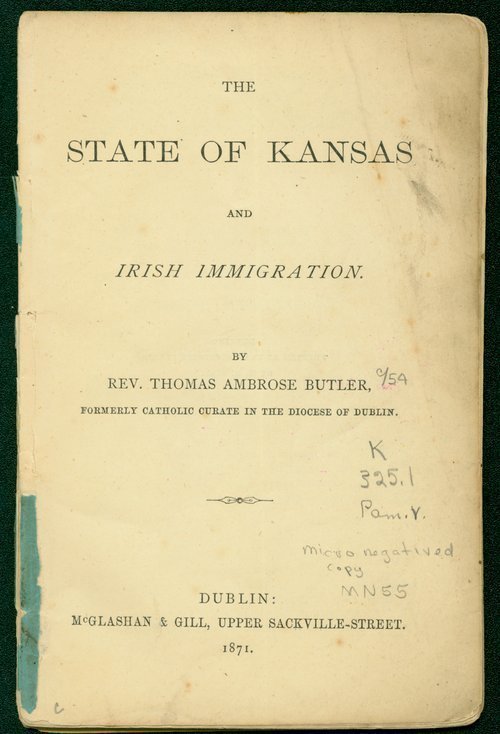

Thomas Butler's account of the life of the Kansas Irish was published as a pamphlet titled The State of Kansas and Irish Immigration in 1871. It was an effort at demonstrating how Kansas's fertile prairies were among the best farming land in the United States, and how those seeking to immigrate to America ought to consider moving to the Sunflower State where "you may soon grow rich and independent as a farmer, with yellow corn waving upon the breasts of the prairies, and cattle grazing upon the hills, and no master over you but the Great Lord of Heaven and Earth."[12] Butler wrote that in 1870 the Irish made up 1/6th of the population of Leavenworth, or around 4,000 out of the city's total population of 25,000.[13] They earned on average around $1.50 per day's wages in cities like Leavenworth, leading Butler to argue strongly that the best option for the Irish was to leave the cities behind and become independent "farm labourers" in the countryside.[14]

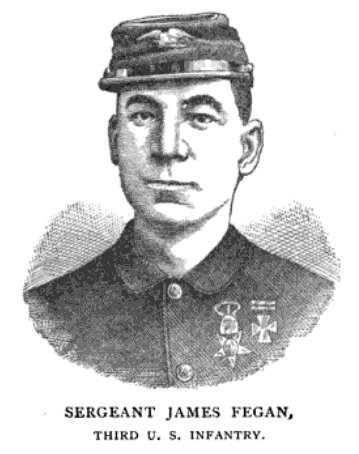

Few Irish settlements were established in the 19th century in the western half of the state, only New Almelo in Norton County and Herndon in Rawlins County in northwestern Kansas had significant Irish populations.[15] Still, Irish immigrants could be found in western Kansas among the soldiers stationed at the Army's forts that lined the wagon trails and railroads stretching across the high plains towards the distant Rockies. In 1870 there were 22 such Irish soldiers stationed in the Kansas forts, making up 18% of the total US Army presence in the state, a startling number on several levels.[16] One of these was a sergeant from Athlone named James Fegan (1827–1886) who served in the 2nd Infantry from 1851 through the first two years of the Civil War when he was seriously wounded at Antietam.[17] Fegan later re-enlisted in Company C of the 3rd Infantry in March 1864 and saw action in the Army of the Potomac at the Battles of Petersburg and Richmond. He was present at Appomattox Courthouse when General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia surrendered ending the war.[18]

After his service in the East, Sergeant Fegan was deployed to the frontier during which he "participated in numerous thrilling experiences besides pitched battles" against Native American raiding parities and army deserters. In one such encounter on 13 March 1868 at a place called Plum Creek along the road between Fort Harker and Fort Dodge, Fegan was attacked by a sergeant from the 7th Calvary "aided by some citizens" to free "a deserter, whom [Fegan] had recently apprehended." Fegan refused to hand over his prisoner and single-handedly stood guard over the deserter, driving off the wayward sergeant and his posse by igniting the gunpowder barrels carried by his mule train.[19] For his heroism, Sergeant Fegan received the Congressional Medal of Honor with a citation that reads: “While in charge of a powder train en route from Fort Harker to Fort Dodge, Kan., was attacked by a party of desperadoes, who attempted to rescue a deserter in his charge and to fire the train. Sgt. Fegan, singlehandedly, repelled the attacking party, wounding two of them, and brought his train through in safety.”[20] Though he did not settle in Kansas, instead choosing to retire to Montana, Sgt. Fegan's heroism reflected the commitment the Kansas Irish had to growing their communities across the state.

By 1884 the Irish settlements that Fr. Butler recorded a decade earlier had grown into some of Kansas's many farming towns. In that year there were 12 divisions of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) active across the state. Of these one was located in Johnson County, its officers living mostly in Edgerton, Gardner, and Olathe. There were also divisions based in Atchison, Topeka, Scranton, Osage City, Saint Marys, Scammonville, Weir City, Kansas City, and Armourdale. One division of particular note was the Pottawatomie County Division 1, located in Blaine, a town originally named Butler City after its founder, the pioneer priest Fr. Butler of Leavenworth.[21]

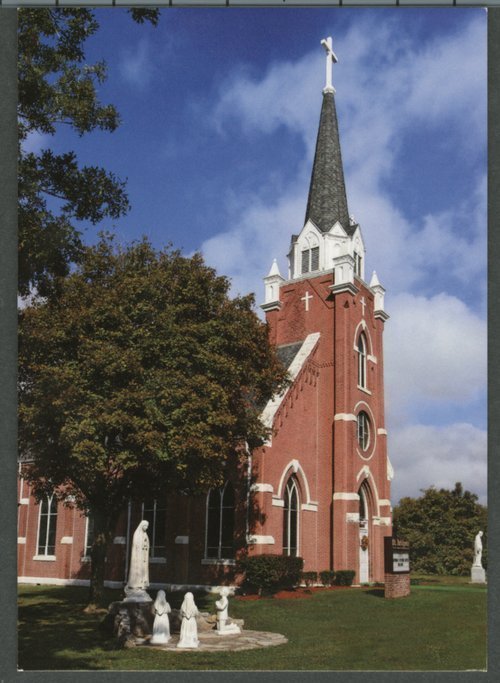

St. Bridget’s Church, Scammon KSHS 221897

The Kansas Irish have always been closely and emotionally attached to their ancestral homeland. Fr. Butler made it clear that immigration ought to be an option of last resort for Irishmen, warning his countrymen "do not come out to America if you can live at home. If you cannot live in Ireland, come out and till the fertile prairies and you will be happy."[22] Butler wrote from the heart that "the pang of separation, and the subsequent sad feeling of exile from friends and the old country, leave an impress upon the heart that cannot be removed" and that only the "one class in Ireland" who "has no other resource left but emigration" ought to relocate to Kansas.[23] In the seventh verse of his poem New and Old, Fr. Butler wrote of how the Kansas prairie was at times a lonesome home for the Irish immigrant, writing:

“Around “the Settlement” gazing, the Exile

can never behold

A scene to remind him of Erin––a home

like his fathers of old.”

Fr. Butler's poetry and songs speak to this moment in the Kansas Irish experience. His prologue spoken in verse to an Irish American Dramatic Club in Leavenworth hails "the exiles far from Erin's shore!" who joined together as one people far from home to celebrate St. Patrick's Day around 1870.[24] "We meet, the young, the old––Hibernians all!" for while his community may have become Americans they still never forgot their homeland.[25] This spirit marks the Irish American community more generally as emotionally bound together through the common memories of immigration, "exile" in Fr. Butler's words, and the struggle to find a new home in America. The Kansas Irish found an experience different from their kin who settled in the East or Great Lakes regions as they built their own communities from the ground up, new settlements across the Kansas prairies following the rivers, wagon trails, and railroads across the landscape.

Fr. Butler’s pamphlet encouraging Irish immigration

Life in a New Home

At the turn of the 20th century the Kansas Irish numbered 11,516, comprising 9% of the total state population.[26] In the 1902 AOH National Directory there were 7 divisions located in Kansas, two in Cherokee County in Scammon and Weir City, two in Crawford County in Pittsburg and Greenbrush, one in Leavenworth, one in Topeka, and one in Kansas City. Of the 1884 divisions, only the two Cherokee County divisions, the Topeka division, and Wyandotte County's Division 2 remained. The decline of the AOH in the state likely reflects a greater distance from the immigrant generation who settled Kansas's Irish towns in the 1850s through 1870s. Still, David Emmons records a long list of Kansas cities and towns that contributed to the Irish nationalist cause in the 1880s and in 1905, including the Topeka, Atchison, Edgerton, Gardner, Olathe, and Wyandotte Irish communities, as well as Irish servicemen stationed at Fort Leavenworth and new arrivals in Reno County.[27] In 1919, President of the revolutionary Dáil Éireann, Éamon de Valera (1888–1975) visited Kansas City, Missouri during his first American Tour to raise money for the Dáil as the revolutionary Irish Republic's government during the Irish War for Independence of 1919–1922.[28]

Éamon De Valera, President of Dáil Éireann, 1919-1922 at the time of his US Tour

The world wars saw many Irish Americans serve on the frontlines. Some, like Sergeant William Shannon from Bourbon County would give everything in that service. Shannon was born in January 1896 in Timberhill, Kansas, the youngest of 6 children. His parents William and Mary were both Irish immigrants, though it's not clear where in Ireland they were born. His father arrived in America in 1862 a boy of 11 at the height of the Civil War. While he did not see service in that war, his son Edward would in 1917 and 1918 in France. Serving as a Sergeant in a machine gun company, Edward Shannon was wounded in battle in the Bantheville Woods where his company was sent to support the 353rd Infantry's 3rd Battalion in the Meuse-Argonne offensive in late October 1918. On November 1st, Shannon's company "moved out into 'No Man's Land' and 'dug in.'" Just after 5 am as his company advanced Sgt. Shannon "was mortally wounded by enemy machine gun fire."[29] He died the following day from his wounds and is buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France.[30] Sergeant Shannon was one of many Kansas Irish to serve in the Armed Forces in the World Wars.

Sgt. Edward Shannon’s headstone. Source: soilsister, Find A Grave

The Irish communities across Kansas made their presence known in the state's geography by naming their parishes and churches after Irish saints. As J. Neale Carmen wrote, "Churches dedicated to Saint Patrick or Saint [Columcille] or Saint Bridget are almost certain to be serving Irish clientele, and names that refer to the Virgin Mary like Immaculate Conception and Assumption are more likely to have been chosen by the Irish than by another group unless it were Spanish-speaking."[31] Notable among these are the town of St. Bridget's in Marshall County on the Nebraska border, and St. Columbkille's Church in Fr. Butler's town of Blaine.[32] Among these parishes dedicated to Irish saints is St. Patrick's "built by Irish farm families in Wyandotte County in 1873." Carman quotes a May 1957 article in the Kansas City Star which announced that the old church was being torn down to be "soon replaced by something much more pretentious."[33]Yet by this point, the population of St. Patrick's had shifted from being half-Irish, half-German as it was at its founding to being "mostly those of Slavic origin who had moved out from the Strawberry Hill district of Kansas City, Kansas." Carman continued that at that point then pastor Fr. William Dolan "expressed doubt that the parish was primarily Irish within any recent memory."[34] Similar changes in population occurred across most of the settlements founded by the Kansas Irish as people moved out of old farming communities at the beginning of the 20th century to the cities.

St. Patrick’s Church, Kansas City, KS built in 1957

One such Irish Kansan to move from farm to city was Ellen Quinlan, born in Parsons in 1889 the twelfth of 13 children of an immigrant railroad worker from County Cork. She stayed in Parsons through her high school years, graduating from Parsons High School in 1907, at which point she moved 150 miles northeast to Kansas City, Missouri where she started work as a stenographer and married her first husband Paul Donnelly. Her 1991 obituary in the New York Times records that she first started making dresses in 1916 "to replace the drab, cotton house dresses of the period."[35] Pat O'Neill records in his history of the Kansas City Irish, From the Bottom Up, that she "took a sample of one of her pink gingham dresses to the manager of Peck Dry Goods" who ordered 18 dozen "on a whim" which she priced at $1 each, 31 cents higher than the average that year. "Those first 18 dozen," O'Neill writes "sold out at Peck's in one day."[36] Out of this first sale grew the Donnelly Garment Company made famous by its Nelly Don label established in 1919 with an early production center located in the Western Auto building at 21st and Grand in Kansas City, Missouri. Nelly Don became famous for its strong work culture, her company was among the first in Kansas City "to offer paid group hospitalization for employees and an unlimited number of tuition-paid night courses and scholarships for their children at local colleges."[37] In 1931, Nell Donnelly and her chauffeur were kidnapped in what became a national scandal with their ransom at $75,000. Her captivity in a house in Bonner Springs ended after 32 hours and she soon divorced her husband to marry the prosecutor in her kidnapping case, former Senator James A. Reed. Nell Donnelly Reed's story is one of many successes in the history of the Kansas Irish.

Nell Donnelly Reed (1889–1991)

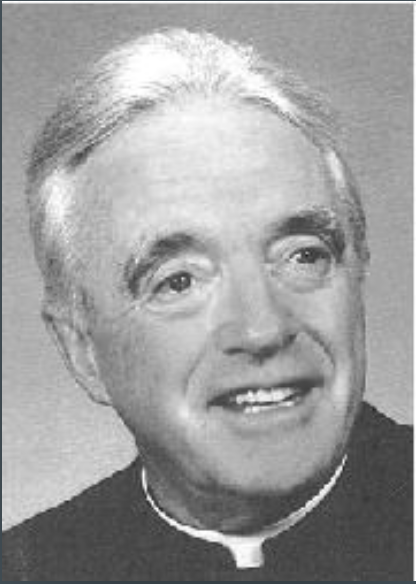

By the 1950s the Kansas Irish communities were well settled across the state. While many rural Irish towns continued to prosper newer communities were established in larger towns like Hutchinson that previously were not as strongly Irish. In 1950 a young priest from Mourneabbey Parish in northwest County Cork named Fr. Sean O'Shea (1924–2017) arrived in Wichita to serve as one of several newly arrived Irish priests in that diocese. During his 67 year ministry in the Diocese of Wichita, Fr. O'Shea served at parishes in Fort Scott, Fulton, Little River, Halstead, Kingman, Hutchinson, and Wichita.[38]Still, Fr. O'Shea's passion for his homeland reflected many of the Kansas Irish, for whom the common bond to Ireland has remained a uniting factor even as the generations draw these communities further from their immigrant ancestors. New arrivals to Kansas from Irish communities further east have added to the diversity of the Kansas Irish.

Fr. Sean O’Shea (1924–2017)

The new millennium has seen a resurgence among the Kansas Irish as new generations become more aware of their roots and contribute to this story. In 2002 the Ancient Order of Hibernians returned to the Sunflower State with the establishment of the Fr. Bernard Donnelly Division in Johnson County. Today, the Kansas Irish population has reached 330,000, making up just over 11% of the state's population. 35% of the Kansas Irish today live in the Greater Kansas City Area, and they make up 46% of the total cross-border Kansas City Irish population.[39] The Greater Kansas City area has become known globally as a center of the Irish diaspora. At the start of the 2020s the AOH has begun to expand across the state with the new Fr. Sean O'Shea and Fr. Thomas Butler divisions being established in Hutchinson and Leavenworth respectively in 2022.

The Fr. Donnelly Division AOH Kilt Crew Honor Guard at the National World War I Museum and Memorial, 2022

Conclusion

The history of the Kansas Irish reflects the broader history of the American settlement of the Great Plains. Irish settlers established their own communities here and built new homes and lives amid the prairie grasses, never forgetting what they left behind. While colorful characters like Patrick Gass, George Shannon, Pat Devlin, James Fegan, and Nell Donnelly Reed are prominent in the state's Irish history, the many thousands of unnamed Kansas Irish who settled this state and continue to call it home are the heart of this history. Their story continues to be written.

Seán Thomas Kane is a historian of science and natural history in the Renaissance. He is also the creator of The Wednesday Blog podcast. Kane currently serves as Historian and Archivist of the Kansas State Board of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and was honored by the Fr. Bernard Donnelly Division with the 2022 John T. O’Neal Sr. Hibernian of the Year Award. Kane has been a Hibernian since 2009.

Sources

[1] Patrick Gass, A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery, (Pittsburgh: Zadok Cramer, 1807), 19. Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804–1806, Vol. 1, (New York: Dodd, Mead, & Co., 1904), 58–62.

[2] Larry E. Morris, et al., The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers after the Expedition, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 32.

[3] William J. Dalton, The Life of Father Bernard Donnelly, (Kansas City, MO: Grimes-Joyce Printing Co., 1921), 49, 55–57.

[4] James A. McGonigle, "Missions Among the Indians of Kansas: Right Reverend John B. Miège, S.J., First Catholic Bishop of Kansas," Kansas Historical Collections, 9 (1905–06), 153–159, at 155.

[5] Thomas Ambrose Butler, The State of Kansas and Irish Immigration, (Dublin: McGlashan & Gill, 1871), 11.

[6] Kansas State Census, 1859, Lykins County, p. 9.14.

[7] Frank Baron, “James H. Lane and the Origins of the Kansas Jayhawk,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 34 (2011): 114–127, at 119.

[8] Muster roll, Burlingame Rifles Company C, 1857, James Abbott Collection, Collection 252, box 2, folder 10; Baron, 119, n. 14.

[9] T.F. Robley, History of bourbon County Kansas to the Close of 1865, (Fort Scott, KS: The Monitory Book & Printing Co., 1984), 95; Baron, 117–118.

[10] Mary Donnelly, History of St. John's Church, Lawrence, Kansas (1904), KSHS 225617, 2.

[11] Donnelly, 4.

[12] Butler, Kansas, 5.

[13] Butler, Kansas, 12.

[14] Butler, Kansas, 13.

[15] J. Neale Carman, "Kansas Irish Settlements" in Rural Settlements of Irish in Kansas, p. 20, in Immigration history collection, MS Coll. 587-B.

[16] David W. Emmons, Beyond the American Pale: the Irish in the West, 1854-1910, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 215, Table 4.

[17] Theo F. Rodenbough, ed., Uncle Sam's Medal of Honor: Some of the Noble Deeds For Which the Medal Has Been Awarded, Described By Those Who Have Won It, 1861-1866, (New York: G.P. Putham's Sons, 1886), 394.

[18] Rodenbough, 394.

[19] Rodenbough, 395.

[20] Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs, Medal of Honor recipients, 1863-1973, 93rd Congress, 1st session (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1973), 289.

[21] Third Annual Directory of the Ancient Order of Hibernians of the United States, Containing the Names and Addresses of All National, State, County, and Division Officers, 1884-85, (Dayton, OH: Sweetmna's Book & Job Printing House, 1884), 69–70.

[22] Butler, Kansas, 37.

[23] Butler, Kansas, 5.

[24] Butler, Irish, 111.

[25] Butler, Irish, 112.

[26] Emmons, 214, Table 3.

[27] Emmons, 352–354.

[28] Helene O'Keeffe, "De Valera's American Tour, 1919–1920" University College Cork, The Irish Revolution Project, 24 March 2020, https://www.ucc.ie/en/theirishrevolution/collections/mapping-the-irish-revolution/de-valeras-american-tour-1919-20/.

[29] Charles F. Dienst, et al., History of the 353rd Infantry Regiment, 89th Division National Army, September 1917 to June 1919, (Wichita, KS: The 353rd Infantry Society, 1921), 244.

[30] "Edward Shannon," in Kansas Soldiers of the Great War, 1917-1918, Kansas State Historical Society, 1921. Shannon is buried in Plot C, Row 33, Grave 36.

[31] Carman, 2.

[32] Carman, 7–9.

[33] Carman, 5.

[34] Carman, 5.

[35] Lena Williams, "Nell Donnelly Reed, 102, Pioneer In Manufacture of Women's Attire," The New York Times, 10 September 1991, Section B, Page 5.

[36] Pat O'Neill, From the Bottom Up: The Story of the Irish in Kansas City, (Kansas City, MO: Seat O' Pants Publishing, 2000), 155.

[37] Williams, 5.

[38] "Rev. John J. O'Shea Obituary," Wichita Eagle, 29 November 2017.

[39] US Census Bureau 2021 Irish American Population Estimate, (March 2021).